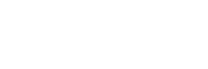

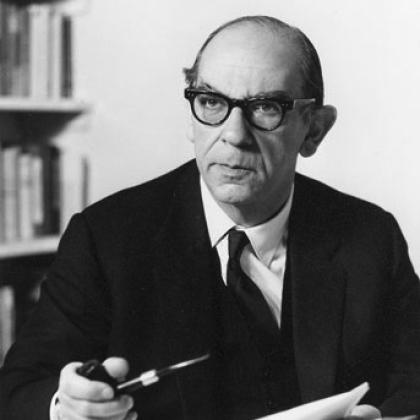

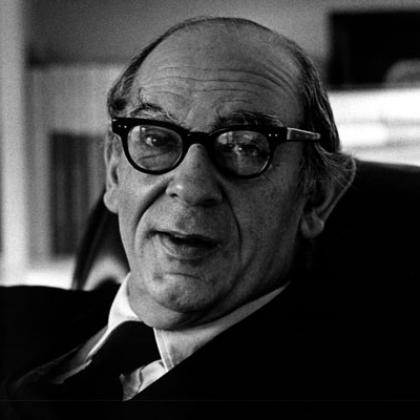

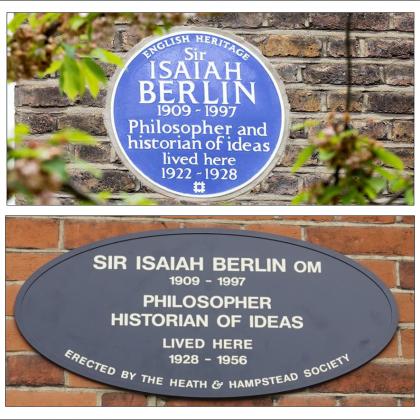

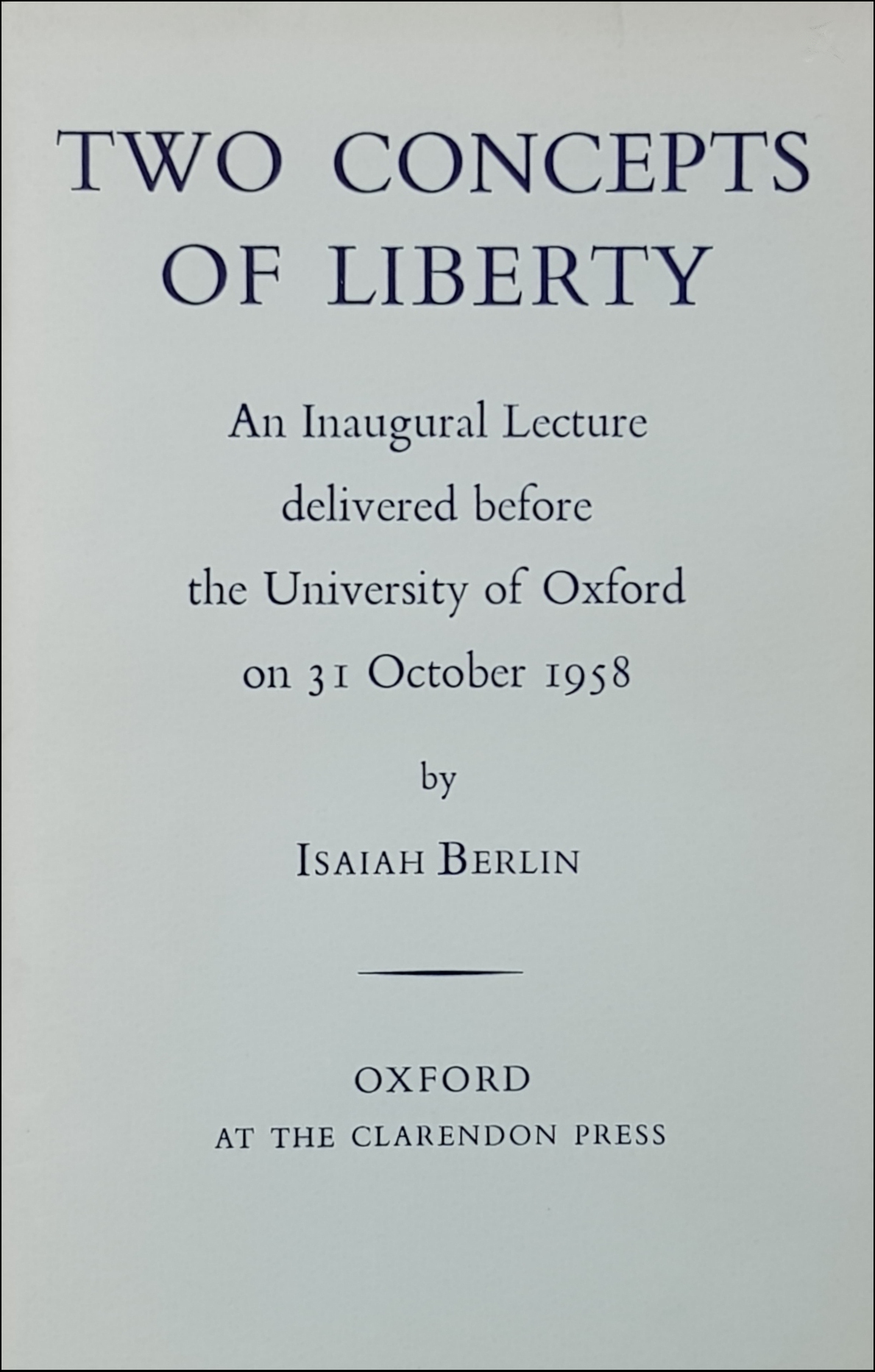

Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997) was an Oxford philosopher and historian of ideas, who made a key contribution to the development of political theory with his essay 'Two Concepts of Liberty' (1958). More famous still is his study on Tolstoy's view of history, The Hedgehog and the Fox (1953). His writings on liberty and pluralism are a part of the intellectual bedrock of the open society. The best concise biography of Berlin is Alan Ryan's article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

One way of approaching Berlin's life and works is through his admiration for, and identification with, the 19th century Russian writer, radical, and publicist, Alexander Herzen. Berlin came upon Herzen's works by chance in the London Library while researching his biography of Karl Marx (1939). It was an accidental discovery that had important consequences. Berlin came to regard Herzen as 'the most eloquent and convincing preacher' of a fundamental truth – that monist systems of thought are responsible for inhumanity and injustice on a colossal scale. He believed that 'political fanaticism of this type, no matter how pure the motive, how noble the goal, invariably leads to blood', and that no century illustrated this 'in a more dreadful fashion' than his own. He recommended Herzen as the antidote. Read more about Isaiah Berlin, Alexander Herzen, and 'the Pursuit of the Ideal'.

John Banville, New York Review of Books , 19 December 2013

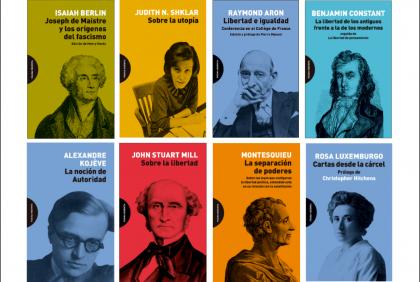

Isaiah Berlin's essay ‘Joseph de Maistre and the Origins of Fascism’, probably begun in the 1940s, was not completed until 1960. In 1990 it was included in the anthology The Crooked Timber of Humanity (ed. Henry Hardy). And in 2021 it was published by the Spanish publisher Página Indómita, translated by Roberto Ramos. This latter edition is one in a series of foundational texts published by Página Indómita that includes works by Alexandre Kojève, Judith Shklar, Raymond Aron, Rosa Luxemburg, Benjamin Constant, Montesquieu, and John Stuart Mill (all pictured).

All of these details, and more, can be found in the Isaiah Berlin Catalogue.

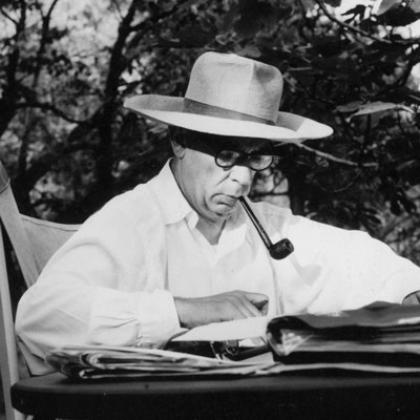

The Isaiah Berlin Image Database ('IBID') is a searchable database of many hundreds of photographs that illustrate Isaiah Berlin's life and times.

Pictured below is the Pelican Essay Club of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 1930, where Isaiah Berlin was an undergraduate (1928–32): he is seated in the front row, third from the right. For identification of those around him see the image and its metadata in the IBID: search on 'Corpus' and then click the image for the metadata.

The database can be searched on keywords, and by date/date range. Copyright queries should be sent to berlin@wolfson.ox.ac.uk

‘Very well: I can only say that I hope the book may be called: Three Critics of the Enlightenment, and will consist of three studies [on Vico, Herder, and de Maistre]. [...]. The issue between the advocates of the enlightenment and these critics is today at least as crucial as it was in its beginnings, and the fashion in which the rival theses were stated in their original form is clearer, simpler and bolder than at any subsequent time’. (to Elizabeth Jennings, 8 March 1960)

‘Again, you are quite right to wonder whether my ‘empathy’ does not go too far. When I write about someone to whom it seems to me historical justice has not been done, whose ideas are more original, have more in them, are more important and sometimes even valid, than is allowed for by conventional accounts, I do probably get carried away and begin to speak with their voices, or at least their voices as I hear them; this must make it seem to some people that I am too empathetic, for Hamann or de Maistre and their progeny are real and dangerous enemies of the Enlightenment and against what I myself believe in; and since I write with equal enthusiasm about unquestionable ‘progressives’ like J. S. Mill or Herzen or Belinsky, or a sceptical but sufficiently anti-reactionary liberal like Turgenev, the reader doesn’t know what to think; I seem to be ‘representing’ all these opposed clients.’ (to Michael Moran, 29 September 1981)

'In the end I come down on the side of the Enlightenment, but the other side should be listened to: they have identified grave flaws, they have a vision too.' (to Mark Lilla, 13 December 1993)

'Jewishness did not have that dominant an influence on all I was and did and thought and felt as, according to Aline, you say. It was not a burden I ever carried, and not an attribute I ever felt made a difference to my philosophical opinions, to my friendships, to any form of life that I lived. I felt a Jew exactly as I felt I had two legs, two arms, two eyes – nothing to be proud or ashamed of, just an attribute, something one was, something one couldn’t help be. Some people didn’t like it, but I was perfectly comfortable with it, always. Consciously, it didn’t make a difference to anything I was or did. (notes sent on a tape cassette to Michael Ignatieff, 30 December 1996)

‘One of the great splendours of the Russians in the nineteenth century, it seems to me, is that, in spite of their fascination by foreign doctrines and their view that truth does exist, that it can be discovered, that one has to suffer for it, that one can then attain it and, having discovered it, one can then devote one’s life to realising it on earth – so in spite of all this, their emotions and imaginations are so active and their sense of individual experience is so concrete and sympathetic (as opposed to their sense of social or political or economic reality, which is feeble) that when it comes to the point they don’t act like fanatical bulldozers, at least in the nineteenth century they did not advocate that in the manner of genuine western doctrinaires. ‘From the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made’ said Kant, and this seems to me to be the central motto of the whole of Russia after the nineteenth century’ (to Elena Levin, 30 November 1954) (find out more)

‘Unmusical cultures exist, but however powerful their impact in other ways, they are characterised by a degree of inhumanity due to lack of an entire dimension of human sensibility, for which there is no substitute or compensation’ (to A. Z. Propes, 15 April 1970)

‘I am truly flattered by your invitation to me to contribute to Opera for its silver jubilee. I suppose I could describe my first experience of Chaliapin singing Boris in St Petersburg in 1916, when I was seven, or Figaro as performed in a cinema in Istanbul where the second act appeared to take place in a seraglio (will this compromise my Turkish visa for ever?), or the occasion during German inflation when Siegfried’s horses ate Hagen’s beard (alas, I did not see this myself, but Nicolas Nabokov says he did; I wonder if it is cheating to describe this as having happened to him). In short, I could probably produce a brief farcical piece which would provide hideous evidence for Peter Hall’s view that people are merely patronising about opera, but whether I can get this done by, or soon after, Christmas is a problem, as I have a terrible term before me, but I will do my best and warn you if the enterprise fails. Do not count on it!’ (to Harold Rosenthal, 7 November 1974)

‘The only occasions, I think, on which I am filled with religious feelings are not at church or mosque or synagogue services (all of which I enjoy up to a point), but when listening to certain types of music – say the Beethoven posthumous quartets’ (to Henry Hardy, 10 February 1992)

‘You ask me what Verdi’s operas mean to me. My love for his music has virtually no limits. […] Verdi’s genius is capable of a deep moral and political grasp of reality, a degree of universal understanding which for me, at least, is without parallel. What more can I say?’ (to the Royal Opera House, 11 December 1995)

'I have listened to more soloists, chamber music, opera, symphonies, choral works than almost, I think, anyone living. This may sound an extravagant claim. My only point is that it is an intrinsic part of my life, not just one of its great pleasures.' (to Michael Ignatieff, 30 December 1996)

‘I’ve just read about Akhmatova’s life, a memoir, a very sensitive & distinguished woman’s reminiscences of her: it is solemn, terribly sad, tragic & full of deaths & – round the nearest corner – torture and executions – & moving as Solzhenitsyn – who is terrifying – is not: because extremely personal and interwoven with old fashioned, noble rules of conduct: of what one does & doesn’t do: what good literary manners are: what one can & what one cannot say (going back to Emily Dickinson or Chekhov or Jane Austen): all this in the midst of unimaginable brutalities, hunger, squalor, blood – in which these ladies – the writer, Lydia Chukovsky, & her heroine, Akhmatova, & all their friends, remain uncontaminated, unbroken, sensitive, articulate, dignified, morally impeccable, not priggish even, and a wonderful, I hope irremoveable reproach to history & E. H. Carr, and all the contemptible ‘impassive’ recorders of the majestic march of the forces of progress’ (to Jean Floud, 31 July 1975)

IB visited Anna Akhmatova in Leningrad in November 1945: 'The fact that I was probably the first foreigner to visit her after more than a quarter of a century did affect her greatly, and in this way I earned an undeserved immortality in her verse' (to Gleb Struve, 19 July 1971). ‘My visit was, I think, the central event of my entire life.’ (to John Russell, 23 January 1995)

'I cannot, alas, get away from specious analogies, but what the Soviet Union seemed to me most like was the severe type of English public school – say Wellington. It isn’t a prison or a reformatory because that depends to some degree upon the feeling of the inmates, who feel hideously confined but not exactly imprisoned. But everything else falls too neatly into the familiar categories.' (to Angus Malcolm, 20 February 1946)

‘I think that it is difficult to imagine a situation in which there was literally no hope left, no hope of that minimum degree of human relationships, of the capacity for any use of thought, imagination, emotional response to anything. It is difficult to imagine this, but not impossible. I simply cast my mind back to my short term of duty in the Soviet Union in 1945, when I asked myself what I would do if I suddenly found myself with a Soviet passport instead of a British one. I was quite clear then that I would wish to blow my brains out rather than try to adjust myself to the system in the hope of better things, or of being able to help others, or the like’ (to Olivia Emmet, 11 March 1982)

‘Tentative offers are made to me to leave my ancient subject and become a Russian historian, an occupation at once better paid and involving less physical and intellectual effort than philosophy. I am delighted to be wooed, but display at the moment a noble austerity of character, saying I could not leave my college in the lurch at its most critical moment, and merely seek my own pleasure; this I hope is producing a profound impression all round, and I shall ultimately be forced to do what I would like to do. At present however my protestations appear to be received on their face value, and I am gloomily contemplating a life of grinding hackery for the next thirty years or so’ (to Phil Graham, 14 November 1946)

‘Philosophy is a fearfully difficult subject, more so with every advancing year. One needs, I am sure, a singular capacity for shutting out irrelevant interests and love of variety, with which I am sadly afflicted’ (to Morton Whilte, November 1950)

'I still believe [...] in the deep truth of that saying of C. I. Lewis that "the truth when it is discovered will not necessarily prove interesting"' (to Charles Taylor, 1962)

‘Oxford and Cambridge philosophy. I was brought up in that movement, empirical-analytic-rational – and remain to a high degree part of it. But what I have in common [with it] is the belief that philosophical thought and language ought to be as clear as one can make it and refer to […] empirical reality, both external and internal – introspective, capable of some degree of self-knowledge, self-understanding, consciousness of hopes and fears and emotions as something in time and not transcendent. In short, I do belong to this school of thought, even though in a moment I shall tell you about some of my differences with it. That is, I neither sympathise with nor really understand the metaphysical tradition that seems to me to prevail in the greater part of the European continent. My ideas are shaped by the English-speaking and Scandinavian worlds’ (to Signora Merlo, 9 April 1991)

‘I am a Zionist, if only because I believe that neither the Jews nor anyone else should be condemned to be a minority everywhere, for that distorts human development, both of individuals and of peoples. Perhaps it would have been better for the Jews if they had been assimilated – disappeared, as the Assyrians and Carthaginians have. But they have not, and their efforts to do so – at least on the part of some of them – have ended in ghastly and humiliating failure, particularly in countries where it appeared that they had been progressing most rapidly and effectively, e.g. Germany at the end of the last and beginning of this century, and Russia in the early years of the Revolution, before Stalin’s real anti-Semitism became permanently respectabilised, de facto, as a widespread attitude in the Soviet Union’ (to Edward Mortimer, 15 April 1983)

‘I only hope that history does not justify your pessimistic interpretation of what Zionism is, and that after the present awful government goes – all governments go in the end – and not necessarily by the destruction of Israel (which has never been impossible), a decent society will emerge, and your analysis will be refuted by the facts. Inshallah.’ (to Kyril Fitzlyon, 16 January 1991)

'Berlin remained a Zionist, but always a liberal Zionist. He was deeply loyal to his fellow Jews, but he deplored narrow tribalism' (Alan Ryan, ODNB)

'American solitude […] induces, at least in me, first a sense of extreme gloom and sense of appalling isolation which undermines all endeavour and causes one to feel that one will never see the familiar world again: […] the reason for never even contemplating the idea of settling in the United States is that such pockets of solitude are built into the very atmosphere itself – human association, in spite of all the warmth and humanity and easiness and lack of strain of certain bits of America, is infinitely more difficult than it is in Europe, and the pauperisation – the process of giving out without taking in – is absolutely remorseless' (to (Stuart Hampshire, 9 October 1961).

‘I am not in the United States at present, although I may be coming for about one week – in and out – to deliver a lecture in Urbana, Illinois, of all places, simply as an excuse for going to the United States – as you may imagine I long to do from time to time – it invigorates me as nothing does, no matter how dark the situation may seem' (to Aubrey Morgan, 4 February 1974)

'Pasternak in his day scolded me for regarding everything truly Russian through enamoured eyes. That's true: in my old age recidivism is setting in' (to Lidiya Chukovskaya, 20 November 1975)

‘The thing which cheered me, when I was there two or three years ago, and now when they come to see me, is the survival of the Russian intelligentsia. I thought it had been killed stone dead by Communism, but not so. There are young men, educated, sensitive, morally sympathetic, with interest [in] and understanding of the arts, literature etc. – I cannot understand how this could have, not exactly survived, but been reborn. There is something marvellous about Russia after all; as Tyutchev said, ‘Russia is not to be understood by the brain’ (to Kyril FitzLyon, 11 December 1990)

‘The Russians are a great people, as I need not tell you, and full of gifts, and will rise; but whether they will rise in some horrible imperialist Zhirinovsky manner, and try and reconquer the Caucasus, the Baltics etc., I don’t know’ (to Shirley Anglesey, 5 April 1994)

'Sakharov is patriotic, Solzhenitsyn nationalistic (would you not agree?)' (to Kyril Fitzlyon, 22 October 1979)

On Solzhenitsyn: 'For me, he is a Soviet man turned inside out, as it were – a mirror-image of his enemies. Still, I prefer the mirror-image to the original, and if I had to march under either banner I know which it would be, although I should do so with appalling reservations, and am glad I do not have to’ (to Myron Gilmore, 12 July 1978)

On Sakharov: 'Sakharov is my man – he speaks with [an] unaffected, unembarrassed, liberal voice, and enormous courage – not very different from Herzen in the last century: certainly the purest and most civilised voice to come from Russia yet’ (to Myron Gilmore, 12 July 1978)

‘I hope you notice the curious attitude to the Jews in Zhivago – Pasternak obviously dislikes being one and has ladled all of his characteristics as one (and they are exceedingly prominent) into a character called Gordon so as to cleanse Zhivago himself of them. It is not a very successful move and his sisters in Oxford feel embarrassed about the result’ (to Arcadi Nebolsine, 23 February 1959)

'Pasternak, to his honour, be it said, was one of the purest poets of our age – everything he writes is poetical, whether it be prose or verse, essays or novels or stories or indeed words in ordinary (in his case very extraordinary) conversation' (to Christopher Barnes, 13 July 1972)